AI scarecrow has Himalayan elephants in sight

Technology

An electronics development platform invented in South Australia is being used to design an Artificial Intelligence scarecrow to stop wild animals such as elephants and monkeys from destroying crops in Bhutan.

Sign up to receive notifications about new stories in this category.

Thank you for subscribing to story notifications.

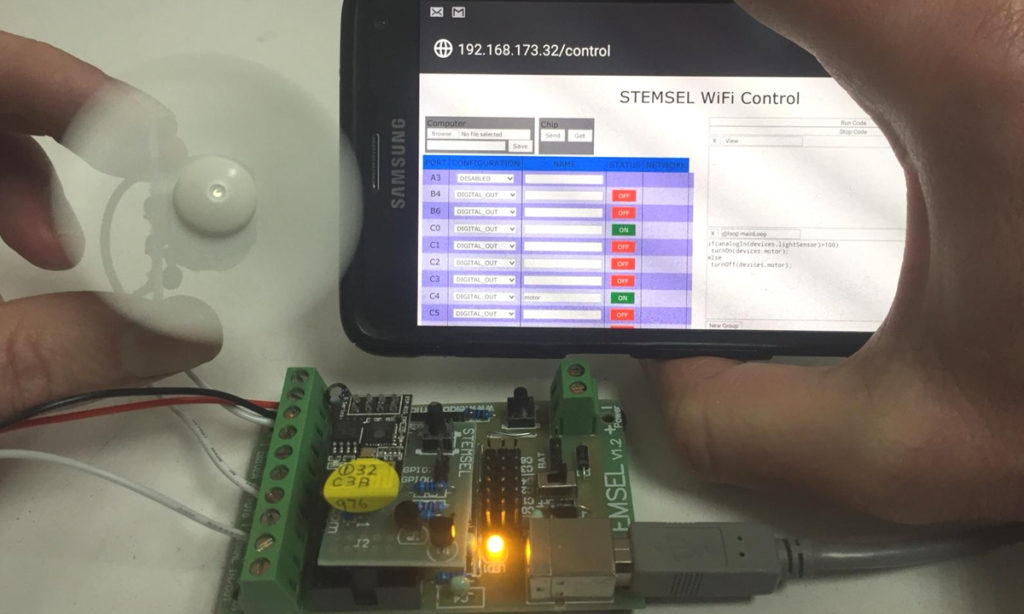

Developed by Adelaide-based company eLabtronics, the runlinc platform allows programming to be done directly onto a microchip. This means it can be done remotely through a Wi-Fi connection, simplifying the creation of Internet of Things and Artificial Intelligence applications.

“It is a very disruptive technology – it is wireless – and one day there won’t be any more cables needed for programming,” inventor and eLabtronics Technology Manager Miroslav Kostecki said.

“For the first time ever, the programming is no longer done inside the computer – runlinc is basically a single web page but it is sitting inside the Wi-Fi chip.”

Bhutanese tech innovator Dupjay Pelzang was alerted to the technology by a colleague in Australia shortly after runlinc received global patent pending status in January this year.

Pelzang was taught runlinc by Kostecki over WhatsApp video conferences spanning six weeks and was the first person in Bhutan to master the platform.

Dupjay Pelzang (right) and other tech workers in Bhutan learn the runlinc program via WhatsApp video sessions.

He is now using runlinc to develop a prototype electronic scarecrow for Bhutan’s government that uses AI and IoT to scare off a range of agricultural pests.

The tiny Himalayan nation only has a population of 800,000, more than half of who work in agriculture. It is the only country in the world with a policy of Gross National Happiness to measure the collective wellbeing and happiness of its population.

However, many of its farmers are not happy about wild animals such as deer, monkeys, wild boars, porcupines and elephants destroying up to 70 per cent of their annual harvest, which includes citrus, potatoes and maize.

This presents a particular problem in Bhutan because of the Buddhist belief that all actions should bring the most help and least harm to other beings. This means agricultural pests cannot be physically harmed using traditional methods such as baits, traps and hunting.

Electric fences have been used in some areas but are expensive, not always effective against elephants, are considered inhumane by some and have resulted in a number of human electrocutions.

Bhutanese tech innovator Dupjay Pelzang (right) explains his scarecrow invention to visiting UNDP Administrator and UN Under Secretary General Achim Steiner.

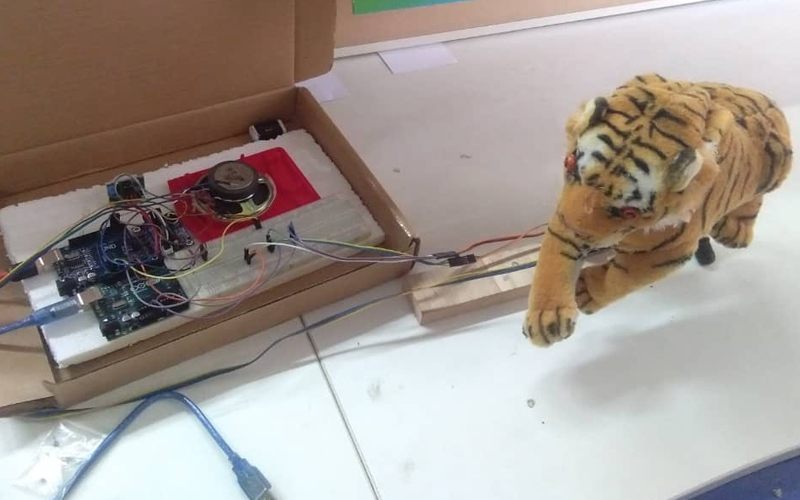

Using runlinc’s technology, the electronic scarecrow, which is designed to look like a tiger, uses a motion-activated camera to detect and photograph a wild animal in a crop zone. The image is then sent to Google for identification. Once a positive identification is made, the scarecrow determines its programmed response.

Pelzang said he aimed to have the final prototype of the team Sung Jab AI Electronic Scarecrow ready for a month-long field trial in July ahead a commercial launch.

He said he aimed to produce 100,000 government-subsidised scarecrows for Bhutanese farmers but also planned for potential sales into nearby India, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

“The (Bhutanese) government has already said they will buy them from me and distribute them to the farmers at a subsidised rate so I am very hopeful that I can sell at least 100,000 scarecrows to the farmers,” Pelzang said.

“It will create jobs for many, many people because one of the main issues in Bhutan is unemployment so in that way I can also contribute.”

The scarecrow will be programmed to recognise five of the major pest animals: porcupine, monkeys, elephant, deer and wild pigs. Scare tactics range from loud noises, flashing lights and movements and vary depending on the target.

The runlinc chip and web page.

“Monkeys are very afraid of the tiger so the scarecrow will produce a high-pitched tiger sound,” Pelzang said.

“Before I was introduced to runlinc I did not know such ideas like this could be integrated into my scarecrow but now I am very confident wild animals can be scared off accordingly.

“To integrate AI things like image detection are now possible. Many other things can be done with the help of runlinc, which are impossible with other technologies.”

The runlinc technology has been in development for the past five years and unlike other electronic prototyping platforms, such as Arduino, runlinc’s development system and corresponding web page is already on the chip, dramatically simplifying the programming process.

Recent benchmark testing of runlinc against Arduino asked a team of six post-graduate students in South Australia to build a web page and create some buttons to control two LED lights.

University of Adelaide student Alex Zhang said the task was completed in 30 minutes with six lines of code using runlinc but with Arduino it took 30 hours and more than 120 lines of code to finish the project.

An early design of the AI scarecrow. A final prototype is due to be completed by July.

eLabtronics CEO Peng Choo said the new development platform was being rolled out as fast as possible “from the ground up” by teaching young people how to use it.

He said the company was in the process of applying for a Centre for Defence Industry Capability (CDIC) grant to teach runlinc to school students as young as eight years old as part of the Australian Government’s focus on STEM education.

“The platforms at the moment are either too simple – like Lego – or too hard like Arduino,” Dr Choo said.

“We’ve actually invented something where suddenly they can do Artificial Intelligence, Internet of Things, they can create their own web pages and little apps from an early age.

“Runlinc is so easy to use that even upper primary school students can get started so can you imagine what it also does for industry when it’s that easy.”

A runlinc inventor’s kit including a Wi-Fi chip retails for A$200. Dr Choo said eLabtronics was preparing to ship parts to Bhutan for assembly and potential sale into the Indian market.

While the possibilities for the technology are almost endless, early uses include DIY smart home kits and IoT enabled sensing devices.

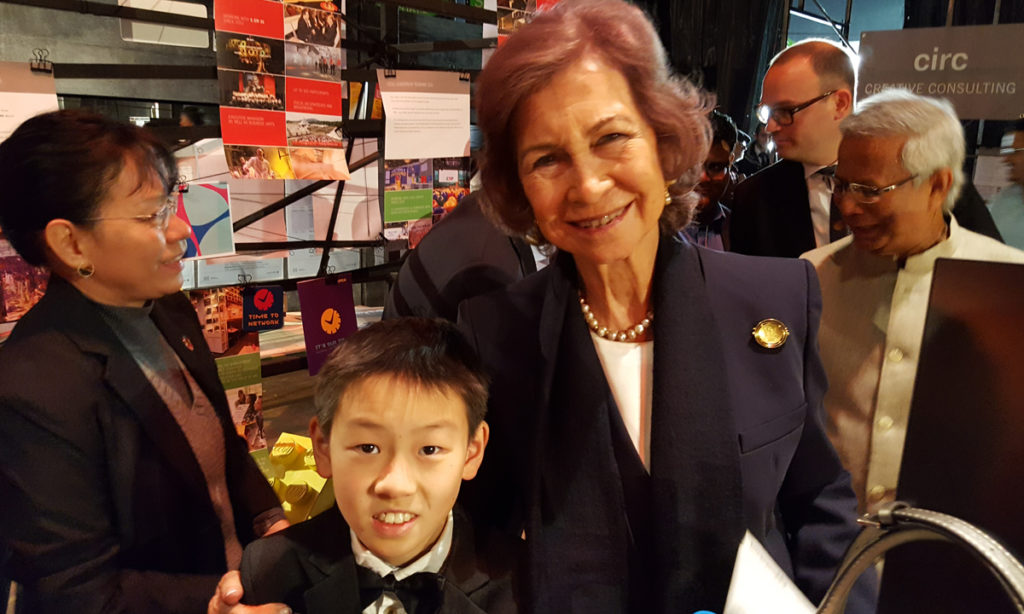

eLabtronics was started by Dr Choo and Kostecki in 1994. It launched an education arm called STEMSEL in 2009. The not-for-profit organisation aims to teach disadvantaged children how to use electronics in combination with Social Enterprise Learning (SEL) and operates in Kyrgyzstan, Cameroon, India, Brunei, Malaysia, Nepal, Thailand, Philippines, Kenya, Bhutan, Australia and the United States.

South Australian student and runlinc user Michael Zhang with Queen Sofia of Spain in Paris.

Pelzang will travel to neighbouring India in the coming months to teach runlinc to 3000 students at the 5000-student SSM College of Engineering near Chennai in the state of Tamil Nadu, which already has links with the South Australian STEMSEL program.

Dr Choo said the model for runlinc was for India to become a centre for its global expansion in the developing world.

“There are 6000 colleges like that operating in India accredited by the top universities and it won’t take more than three months before 3000 students will be training another 3000 high schools.

“They also have international students at that college in India from Nigeria, Kenya, Myanmar and Thailand so it will spread to those places soon.”

“This technology is very much about a change of mindset because this program will run outside the chip.”

Jump to next article