Wombat boom has farmers digging for answers

Primary Industries

Wombats have topped the million mark in southern Australia to reach their largest number in more than a century.

Sign up to receive notifications about new stories in this category.

Thank you for subscribing to story notifications.

However, the rise in numbers is causing major issues for farmers as the furry marsupials compete for food with stock, dig and chew through farm infrastructure and provide hidden pitfalls for machinery.

The explosion of feral rabbits in Australia in the 19th Century crippled wombat stocks, causing them to become extinct in some areas.

But the effective control of feral rabbits through the introduction of viruses such as myxomatosis and calicivirus (RHDV) and the dog fence in the Outback to keep dingoes at bay has been largely credited for the steady increase in numbers of Southern Hairy-Nosed Wombats in recent decades.

University of Adelaide School of Biological Sciences PhD candidate Mike Swinbourne has recently completed the first species-wide mapping of distribution and abundance of the Southern Hairy-Nosed Wombat.

He presented his findings yesterday at the Wombats Through Time and Space conference in Adelaide, the most significant meeting of wombat experts in two decades.

There are three species of wombats: the Southern Hairy-Nosed, Common and Northern Hairy-Nosed Wombat.

There are only about 240 Northern Hairy-Nosed Wombats, all in Queensland, after a brush with extinction that lowered numbers to just 35 two decades ago.

The Common Wombat is more widespread in New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and parts of South Australia but Swinbourne predicts its numbers have been overtaken by the Southern Hairy-Nosed Wombat in recent years.

South Australia is home to 90 per cent of Southern Hairy-Nosed Wombats with the remainder living in the Nullarbor region of Western Australia.

“The arrival of rabbits in the late 19th Century absolutely decimated the wombat population and they even went extinct in some areas,” Swinbourne said.

“I suspect the Southern Hairy-Nosed is now the most abundant species partly because they tend to reside much further from civilization so they escape the worst effects of human encroachment.

“I reckon there’s just over a million on them. We’ve got no idea how many of them there would have been at the time of European settlement but certainly the numbers today are two to three higher than they were 30 years ago.”

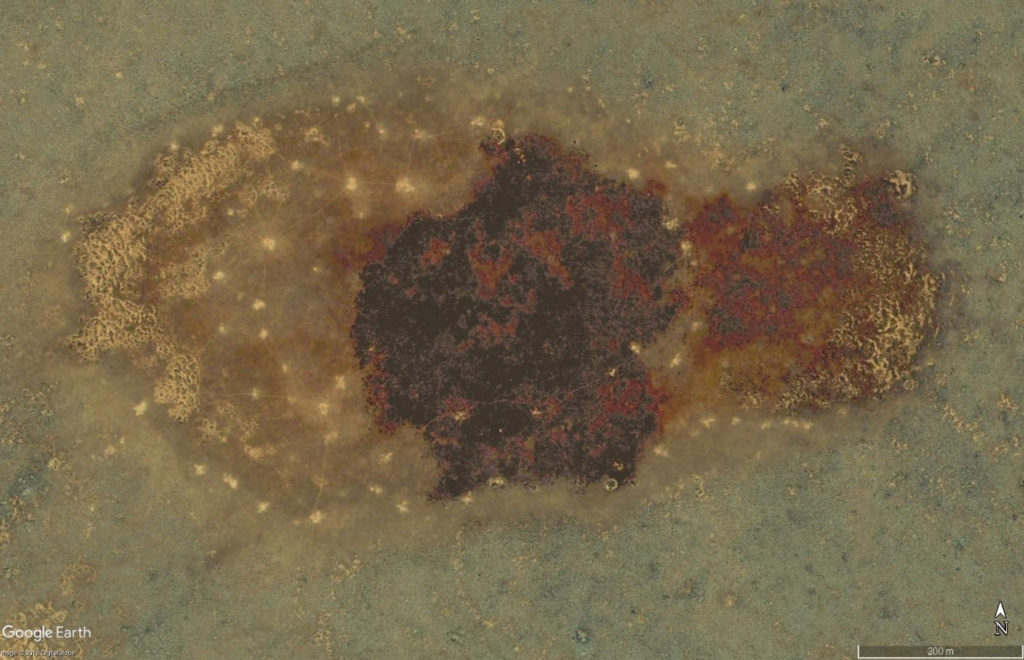

A satellite image from about 45 km north-west of Eucla on the WA/SA border showing a large number of wombat burrows which have been constructed in a claypan depression.

Swinbourne has harnessed modern technologies such as high-resolution satellite imagery and remote motion-activated cameras to give him an accurate population count.

Wombats have previously proven difficult to study because of their nocturnal lifestyle and underground homes that are often in remote areas.

While Swinbourne is delighted with the recovery of the humble wombat, particularly in southern Australia, he acknowledges their swelling numbers are impacting farmers.

Mapping shows the worst affected areas in South Australia to be Eyre Peninsula, Murray Lands, Gawler Ranges, Yorke Peninsula and the Nullarbor Plain.

Wonga Station pastoralist David Lindner runs sheep on a 53,000ha property near Morgan in the Murray Lands, about 160km northeast of Adelaide.

He told the conference that grazing halos around warrens and the damage caused to fences by the burrowing animals had taken its toll in recent years.

Lindner said the impact caused by the boom in wombat numbers along with ongoing issues with kangaroos, rabbits and goats had meant some sections of his land could no longer support commercial sheep production.

“Forty years ago we never had a wombat on our property, today they cover nearly half of it,” Lindner said.

“There’s been an explosion and digging has really escalated in the last 10 years and as a landowner we’re asking why this is happening and what we’re going to do about it.

“They love digging under things like fences and the implications of that are how do I keep the fence standing and then you’ve got the legal implication of what happens when my livestock gets out onto the road and someone hits them?”

The Southern Hairy-Nosed Wombat is the state’s faunal emblem in South Australia, where it is also a protected species under the National Parks and Wildlife Act. About 90 per cent of the wombats are believed to be living on agricultural land.

Destruction permits can be issued when environmental, economic or social impacts are being sustained but farmers say these are often not granted in sufficient numbers to truly address the problem.

University of Adelaide PhD candidate Casey O’Brien surveyed Murray Lands farmers and received 155 responses from landholders in the region.

Eighty per cent of respondents with wombats on their properties reported damage with half of those experiencing more than $10,000 of damage per year.

O’Brien said as well as wrecking fences with their digging, wombats undermine water tanks, chew plastic irrigation pipes and were particularly worrying for cereal farmers.

“Once the crop gets high and is ready to be harvested, a farmer is driving their header through the paddock and can’t see the burrow and it’s not just the burrow entrance that’s the problem, it’s the tunnel system that can collapse under the weight, the machinery falls down to its axels causing serious damage,” she said.

“The worst case I’ve heard of caused $170,000 damage and that farmer now has two headers in case it happens again.”

Despite the destruction, 86 per cent of respondents to O’Brien’s research survey said they supported conservation and the majority said that co-existence with wombats was possible. Fifty per cent said they culled wombats to reduce damage but only half of those said it was successful.

Almost half of respondents suggested developing non-lethal control strategies such as translocation.

O’Brien also conducted a small-scale translocation trial of 13 Murray Lands wombats. While it was believed most of the removed wombats survived in their new locations, neighbouring wombats moved in to their former homes within two weeks of their removal, negating the effect of the translocation.

She has also researched the effectiveness of placing deterrents around warrens such as blood and bone, CDs and the faeces and urine of dingoes, the natural predator of wombats.

But she said none of these deterrents had proved hugely effective.

“There’s definitely support for the development of non-lethal management but unfortunately at the moment we don’t have any successful economically viable options available to landholders and it’s an area that requires a lot more research,” O’Brien said.

“We also need more long term data so we can better estimate the percentage of wombats that need to be culled in order to maintain a stable population while also allowing farmers to manage species on their properties.”

Lindner agreed that researchers and farmers needed to work together to achieve a sustainable solution.

“We’ve got to take a bipartisan approach to this and get the land managers involved – we need to have some structure similar to what the kangaroo industry has had for many years to make sure we can stay on a straight path and get done what we need to do,” he said.

“We need to look at it from a land management perspective and we need to understand that the grass is the key and cropping areas need to have some ability to negate the wombat issue – holes in crops are dangerous.”

Jump to next article