Giant species of trilobite found on Kangaroo Island

Education

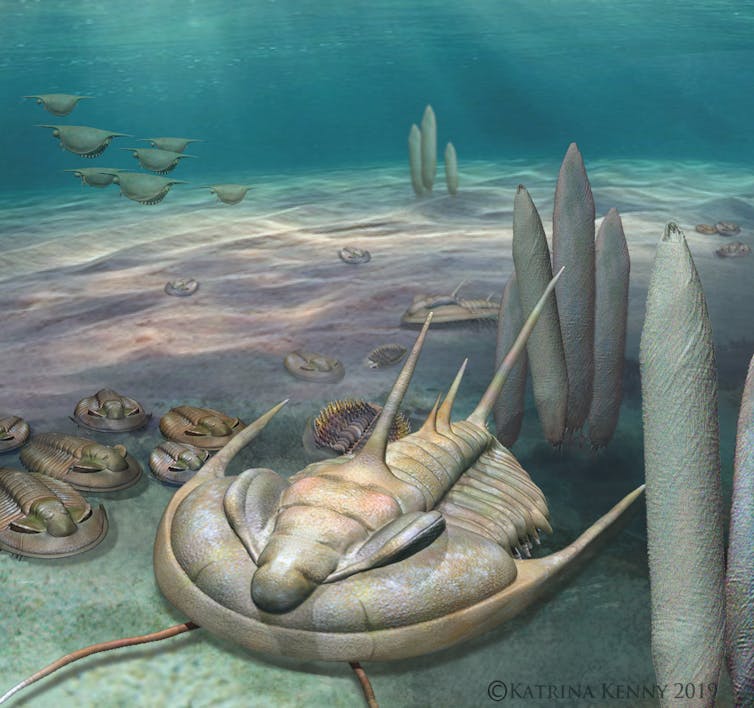

At up to 30cm long and armed with spines for crushing and shredding food, Australian researchers have identified a previously unknown creature that would have been a giant among its neighbours in the waters off modern-day South Australia.

Sign up to receive notifications about new stories in this category.

Thank you for subscribing to story notifications.

The newly described fossil of a trilobite – known as Redlichia rex – is detailed in a paper out this week in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.

There is even evidence this monster of the ancient sea could have been a cannibal, feeding on its own kind.

Trilobites are related to modern-day crustaceans (such as crabs and lobsters) and insects, and are some of the oldest animals to appear in the fossil record.

Because of their abundance, trilobites are considered a model group for understanding the Cambrian explosion – the sudden appearance about 540 million years ago of almost all major animal groups on Earth.

Trilobites first appeared around 520 million years ago and lasted for about 270 million years.

Katrina Kenny, Author provided

Exceptional fossil deposits

Our most important understanding of life around the time of the Cambrian explosion comes from a series of rare, exceptional fossil deposits called Konservat-Lagerstätten (German for “conservation storage-place”).

These deposits preserve not only the hard parts of organisms such as shells, but also the soft parts such as eyes, muscles and guts. The most famous of these is the Burgess Shale from Canada, although a number of other similar deposits have been discovered in places such as China and Greenland.

Australia also boasts one of these deposits – the only one in the Southern Hemisphere. It is called the Emu Bay Shale and is found on Kangaroo Island in South Australia.

The most common fossils within the Emu Bay Shale are trilobites.

The latest find

In the study, the researchers from the University of Adelaide and the University of New England describe a very large new trilobite from the Emu Bay Shale. It’s one of the largest trilobites known from the Cambrian Period.

James Holmes/University of Adelaide, Author provided

Due to its exceptional size and armament, they decided Redlichia rex would be an appropriate name. This is reminiscent of the name Tyrannosaurus rex – rex means “king” in Latin. The Redlichia part of the name is the genus (the same as Homo in Homo sapiens), originally named in 1902 after palaeontologist Karl Redlich.

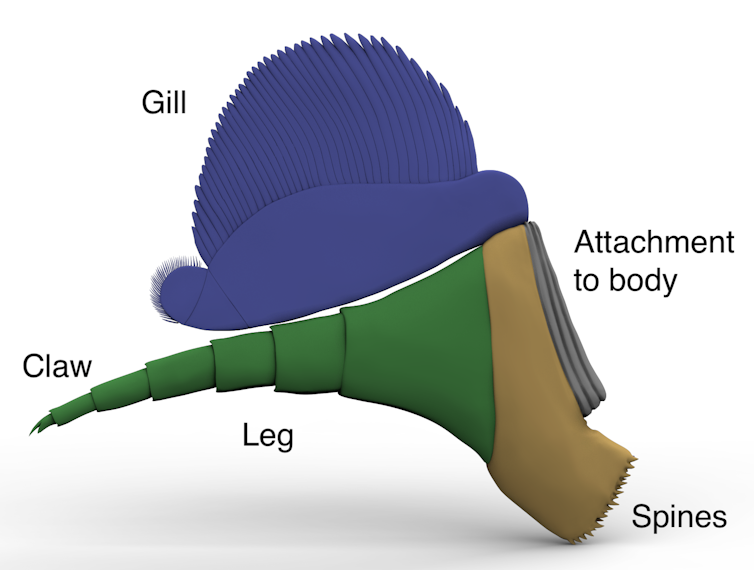

Because the Emu Bay Shale preserves the soft parts of organisms, the appendages (or legs) of trilobites are preserved as well as the hard shell. These soft parts are extremely rare – complete appendages are known for only six of the more than 20,000 described species.

What is even more special about the Emu Bay Shale examples is that because Redlichia rex was so big, the appendages are also very large, making them easier to look at in detail.

Katrina Kenny, Author provided

The most important feature of these is an enlarged inner side of the base of each pair of legs, which was covered in short, robust spines and worked as a nutcracker.

Carnivores of the sea

Unlike those of other trilobites, the morphology of the spines suggests they may have been adapted to crushing shells of other Cambrian animals. If this were the case, the most likely food Redlichia rex would have been eating was other trilobites.

The Emu Bay Shale also contains coprolites, or fossilised poo, in which pieces of crushed-up trilobite have been found.

James Holmes, Author provided

It was originally thought poo fossils such as these were produced by the giant Cambrian predator Anomalocaris – a metre-long beast with two strange claws in the head and a circular, vampire-toothed mouth. But it now seems likely that Redlichia rex produced some of these.

Consistent with this idea, some specimens of Redlichia rex show injuries resulting from attack. These may also be from Anomalocaris, although it is possible that Redlichia rex indulged in cannibalism, or took part in territorial battles (as is seen in modern lobsters).

Once animals began to eat each other, the selective pressure to adapt methods to prevent being eaten would have been very high. This is almost certainly the reason why hard shells evolved in the Cambrian – for protection against predation.

The result would have been an evolutionary arms race between predators and prey, with each developing more efficient ways of defence and attack, such as the development of shell-crushing abilities in certain animals.

The formidable appendages of Redlichia rex are probably a result of this, and this giant trilobite was likely a source of terror for small creatures on the Cambrian seafloor.![]()

James D. Holmes, Palaeontology PhD student, University of Adelaide; Diego C. García-Bellido, Associate Professor, University of Adelaide, and John Paterson, Professor of Earth Sciences, University of New England

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jump to next article