Fossil reveals missing link in getting fish out of water

Education

A global team of researchers reveal how a fish fin turned into a human hand.

Sign up to receive notifications about new stories in this category.

Thank you for subscribing to story notifications.

Leading palaeontologists are revealing how an ancient fossil contains the missing link in how the human hand evolved from fish fins.

Fossil scans scrutinised by an international team drawn from Flinders University in Adelaide, South Australia and the Université du Québec à Rimouski in Canada has led to the breakthrough evidence of how fish progressed into four-legged vertebrates.

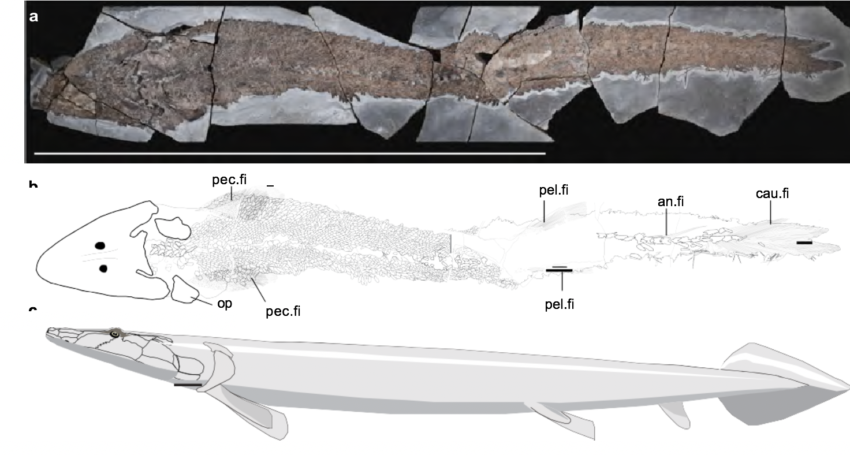

Strategic Professor in Palaeontology at Flinders University Professor John Long said they announced their discovery of a complete specimen of a tetrapod-like fish called Elpistostege in the journal Nature.

“It reveals extraordinary new information about the evolution of the vertebrate hand,” Prof Long said.

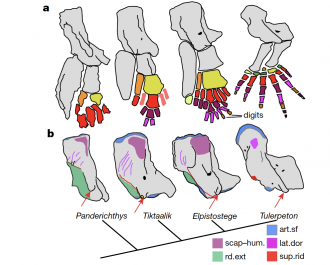

“This is the first time that we have unequivocally discovered fingers locked in a fin with fin-rays in any known fish. The articulating digits in the fin are like the finger bones found in the hands of most animals.

“This finding pushes back the origin of digits in vertebrates to the fish level, and tells us that the patterning for the vertebrate hand was first developed deep in evolution, just before fishes left the water.”

The team used high energy CT-scans to reveal the presence of a humerus (arm), radius and ulna (forearm), rows of carpus (wrist) and phalanges organized in digits (fingers) in the skeleton of a 1.57 metre long fish.

Prof Long said Flinders University is equipped with one of the best labs in the world for analyzing CT data and Canada’s Prof Richard Cloutier spent six months on sabbatical working as a Flinders University Visiting International Fellow leading to the new finding.

Work focused on a remarkable new complete specimen of Elpistostege discovered in Canada during 2010 – Elpistostege was the largest predator living in a shallow marine to estuarine habitat of Quebec about 380 million years ago.

It had powerful sharp fangs in its mouth so it could have fed upon several of the larger extinct lobe-finned fishes found fossilised in the same deposits.

Co-author Richard Cloutier from Université du Québec à Rimouski said over the past decade, fossils informing the fish-to-tetrapod transition have helped to better understand anatomical transformations associated with breathing, hearing, and feeding, as the habitat changed from water to land on Earth.

“The origin of digits relates to developing the capability for the fish to support its weight in shallow water or for short trips out on land,” he said.

“The increased number of small bones in the fin allows more planes of flexibility to spread out its weight through the fin.

“The other features the study revealed concerning the structure of the upper arm bone or humerus, which also shows features present that are shared with early amphibians. Elpistostege is not necessarily our ancestor, but it is closest we can get to a true ‘transitional fossil’, an intermediate between fishes and tetrapods.”

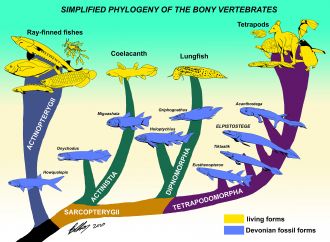

The evolution of fishes into tetrapods – four-legged vertebrates of which humans belong – was one of the most significant events in the history of life.

Vertebrates were then able to leave the water and conquer land but in order to complete this transition- one of the most significant changes was the evolution of hands and feet.

Preparation and CT scanning of the specimen of Elpistostege took place in Quebec in 2010 with Prof Cloutier working with Isabelle Bechard to do the initial interpretation of the scan data, and Vincent Roy and Roxanne Noel to analyse the backbone and fin structures.

A collaboration with Prof John Long and the Flinders University team began in 2014 through Prof Long’s connection with Canadian palaeontologists forged while he was president of the world’s largest palaeontology society, The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

In Adelaide, Dr Alice Clement at Flinders University continued the CT work which revealed details of the digits in the fin.

Prof Mike Lee analysed the phylogenetic data to demonstrate that Elpistostege is now the most evolutionary ‘advanced’ fish known, one node down on the evolutionary tree to all tetrapods.

Prof Long said Flinders University had one of the strongest groups in Australia for vertebrate palaeontology and has recently installed its own high-powered CT scanner signalling “a whole new era of doing our own CT scanning”.

And work would continue on the Elpistostege fish fossil, “this is the tip of the iceberg”, Prof Long said.

Jump to next article