Native Aussie rat survives sticky situation

Environment

Their wooden homes are stuck together with pee and have stood longer than the pyramids.

Sign up to receive notifications about new stories in this category.

Thank you for subscribing to story notifications.

Once abundant across semi-arid regions of southern Australia, the Greater Stick-Nest Rat, Leporillus conditor, was pushed to the brink of extinction in the 20th Century by competition for food from livestock and rabbits and the introduction of predatory foxes and feral cats.

Now the furry little Australian mammal with a blunt snout and large rounded ears is making a comeback.

The rats earn their Greater tag not from their size, they only grow to 26cm and weigh less than 450 grams, but from their large nests.

Picture: Kath Tuft.

According to Nathan Beerkens, an expert Arid Recovery Field Ecologist and Community Co-ordinator, the nests can be up to six cubic metres in size and are built from sticks glued together with the rats’ sticky, odourless urine.

“People have gone out to carbon date them and some of the nests you can still find out in the Outback are over 10,000 years old so they are very good builders,” Beerkens said.

Up to 20 “stickies” live in a nest, which they sometimes decorate with flowers and leaves during breeding season.

“They are nocturnal and spend their days in these huge stick houses that they build. The women are the boss of these houses and they pass them down to their daughters,” Beerkens said.

“After generations and generations they [the nests] can get huge. Sometimes if there are too many [rats living in the nest] they will build their own little granny flat nearby.”

A Greater Stick-Nest Rat nest on Reevesby Island. Picture: Nathan Beerkens.

He said the recovery of the Stick-Nest Rat from the brink of extinction 30 years ago had been amazing.

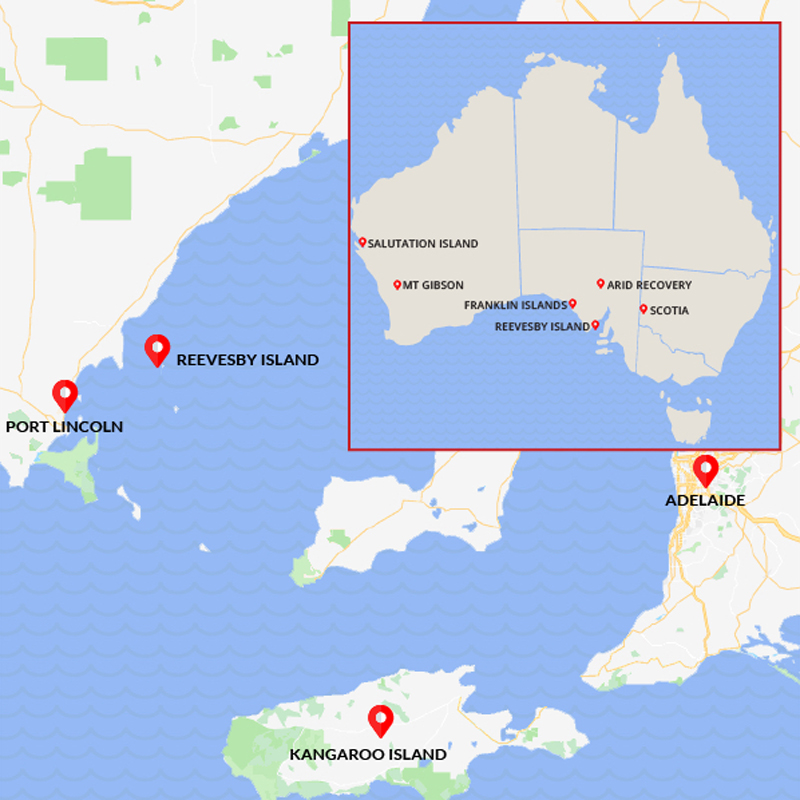

The only surviving natural population of about 1000 Greater Stick-Nest Rats lives on the Franklin Islands off the far West Coast of South Australia.

But a captive breeding program and relocation to several feral free islands in South Australia and Western Australia and within fenced sanctuaries on the mainland is helping the furry little critters thrive again.

The first of 101 of these relocated rats were released on the 400ha Reevesby Island, the largest in the Sir Joseph Banks group of islands in Spencer Gulf, once sheep and feral cats were removed from the island in 1990.

Greater Stick-Nest Rats from the breeding program were also used to populate St Peters Island, near the Franklin Islands, and Salutation Island in Western Australia.

The Reevesby population thrived and 100 of the rats were relocated to the Arid Recovery fenced reserve in Outback South Australia in 1998 and 1999. A further 100 were relocated to the fenced Scotia Wildlife Sanctuary in western New South Wales in 2006.

Almost 30 years later, a team of Arid Recovery ecologists including Stick-Nest Rat experts Peter Copley and Nathan Beerkens visited Reevesby Island in search of the rodents in September.

“We went there with the expectation that there might be none,” Beerkens said.

“We put out Elliott traps and we also went spotlighting and we were fortunate enough to catch 19 of them in a small area but there was evidence of them over the entire island.

A Greater Stick-Nest Rat being released on Reevesby Island. Picture: Kath Tuft.

“It’s hard to say how many animals there are there but it would be in the hundreds and they are going really, really well.”

“The fact that we’ve been able to reintroduce this species from just two islands connected by a sandbar is a real success story as far as Australian conservation goes

“Now that they’ve been spread around so much it really reduces their risk of extinction – it’s a major revival.

“The end goal of all this is to get them living outside of fences on mainland Australia again but that would take a lot of feral control and ecosystem restoration but that is the long-term goal.”

Jump to next article